Use small/mental data to learn how to focus better

The problem:

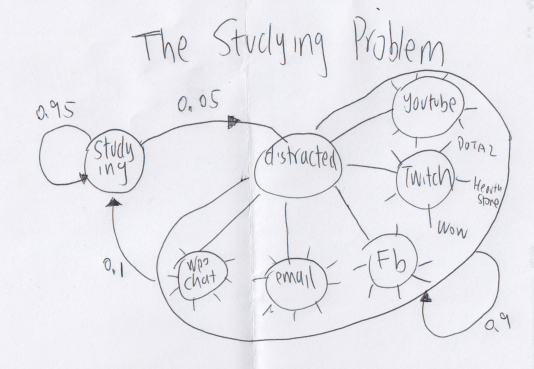

Being able to focus intensely is important for knowledge workers. However, I was often distracted during my studying sessions. Think of studying and being distracted as two different states in a continuous markov chain. Although there is a small rate(probability) of a given moment that I will have the urge to check facebook, email or other sources of distractions, being in the state of distraction at a given moment has a chance of staying distracted. For example, given that I watching a youtube video at the moment, I am very likely to be continue watching in the next moment. Below is an example makov chain of how I see this problem:

Unlike many current machine learning problems, the purpose of this project is not to make good predictions, such as predicting whether I am distracted or not. I only care about if I can focus continuously with minimal distractions, even though knowing that eliminating the urges to run away from studying is almost impossible. To achieve the goal, I want to use as much as knowledge from different disciplines as necessary.

Deep work integration

Idea generation:

This project started as earliest in the last semester. It is started as an experiment from my play of ideas rather than a master plan dedicated to exterminate my focus problem. I was thinking: if I have trouble focusing for more than 30minutes, I could break the whole process down to 5min blocks and try to focus for 5 min at a time. In the end I could just sum up the small, efficient blocks into a larger efficient block like 25, 40 min. To make sure I am focused during the 5 min block, I will write down what I will do in the next 5 min. This idea comes from learning about “heartbeat” in distributed computing: a machine sends a heartbeat is to send messages to other machines “signaling” it is still running normally without failing. By doing so, at least at the end of the 5 min timer, I can withdraw from whatever distractions I have and reengage with my study. Therefore, no single distraction could live longer than 5 min. I called this method “deep work integration,” because the central idea is to integrate(add) many deeply focused work block together to compose an efficient study session.

Implementation:

I first tried this method for a programming project and the results were amazing: I even forgot the flow of time. I was always occupied with finishing the microtask I assigned at the beginning of the 5 min block.

For a while I was applying this technique in many various setting such as making presentation, doing homework, reading textbook and even drawing. A drawing that would normally took me a couple of hours divided from many sessions only took me about an hour an a half in a single session.

Early reflections (like a gradient descent):

Collecting and evaluating feedbacks had been an important element in human learning and machine learning literature. This may sound banal but I often see myself and many others commit mistakes that could have been avoided if we reflect on the past properly. I am grateful for having subconsciously thinking about how to perfect this project, this little experiment of mine. And below are two big flaws I found during my early many reflections:

- My method is bad for tasks that are difficult to make incremental progress in 5 min to log about, such as solving math problems (many problems take me more than 30 minutes to solve).

- The high mental engagement threshold from this method creates high reluctance to use it. Often time I find myself lack the motivation to stay “hyper” focus.

Here are some of the major motifications to address the above flaws:

- Each small study block could now be 5 min, 10 min(default) or 15 min depending on the nature of the work.

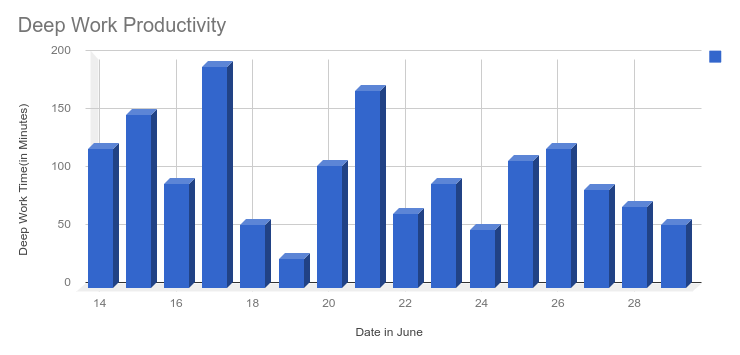

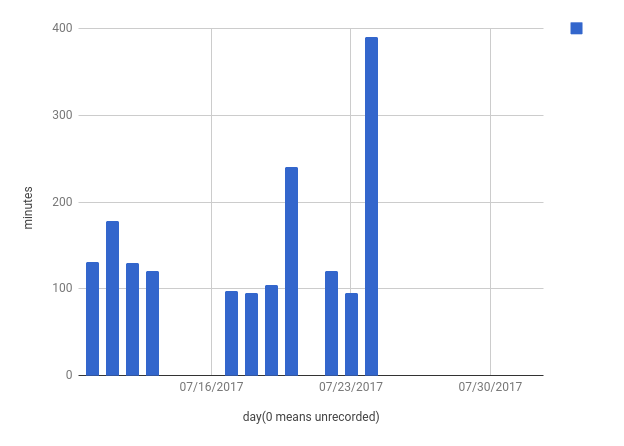

- To motivate me to apply this technique more, I tried to keep track of the total amount of time I used this technique. And first I appended the total amount on google drive document that I used to log my study sessions. Later I created a google drive spreadsheet for this and later made a bar chart to visualize my productivity. I called this technique Daily Integration (my daily productivity is the sum/integration of all my study sessions).

- I gradually allowed myself to take a 5/10min break after 25-50 minutes of efficient studying sessions.

Daily integration

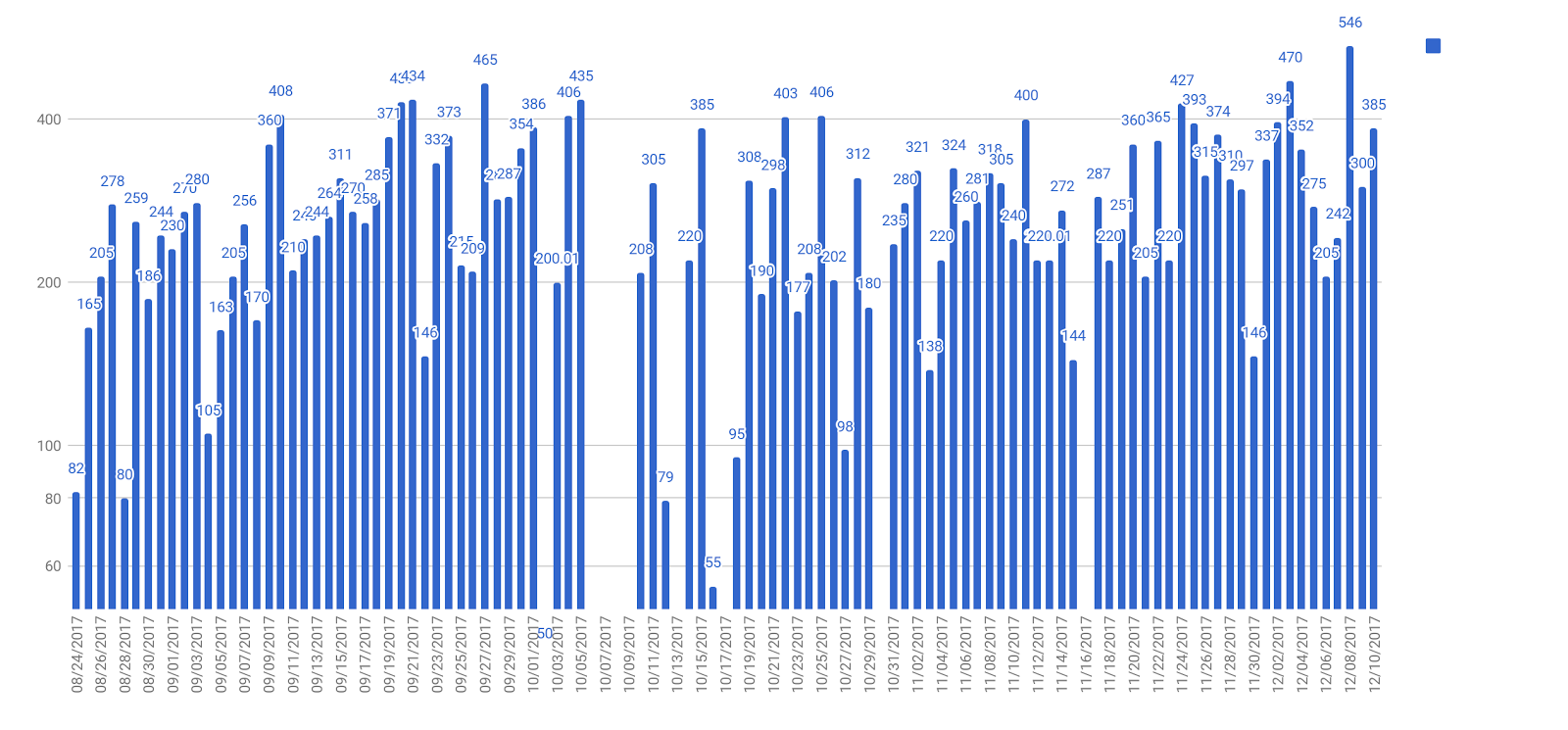

During the summer 2017 I tried to apply the daily integration approach. Below are the charts I made.

From those charts I found that I have not been studying as much. And in many days I didn’t even record any study time.

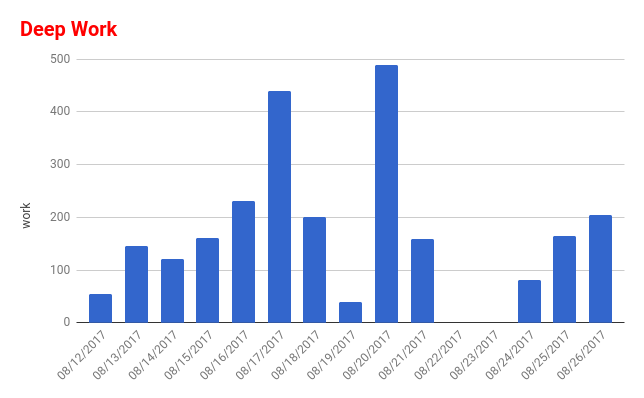

In order to adapt the new fall semester’s heavy workload(stat157 x 2, stat154, math128a and math152), I decided to set up a minimum of 4 hours of studying every day.

Here is the semester productivity:

Starting October, I stopped updating my daily integration minutes in the chart until November 19. I think it was mostly due to stress from homework, midterms and papers. I also got too addicted to a video game called World of Warcraft. I stopped after I formally acknowledged the game was destroying my productivity.

Some reflections(gradient descent):

Here are a collection of thoughts I had been having regarding to the downsides of deepwork integration and daily integration:

- Gradually I increased the use of stopwatch instead of a timer. It was helpful tracking the number of minutes “studied” but I felt like my concentration on average decreased. Without the timer’s pressure, I occasionally would get distracted quickly checking facebook and email updates. I didn’t realize this until recently I had a long, conscious reflection on this project for my presentation,

- Many of my study session ended druing a break.

- My motivation to work decreased drastically after reaching the 4-hour quota, unless there was a deadline.

- This technique did well keeping me focused for a long period of time, however I felt like my prioritization skills got worse because I got lost in reaching the quota thus took less time on thinking what was the right thing to do.

Analysis of breaks

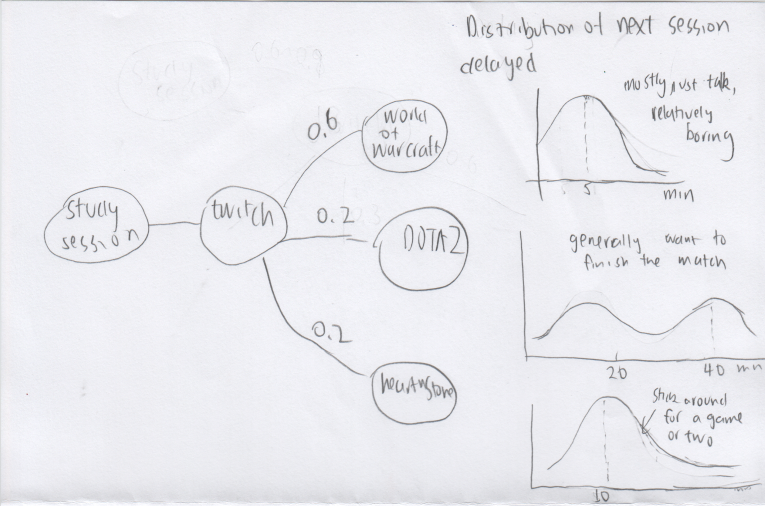

Many of my studying breaks are spent on watching Twitch (videog game live streaming). From tracking my data, I find that watching Twitch most of the time results a delayed in going back to studying. And distribution of the amount of delayed is based on the type of game I watch. Below is a visual markov chain representation of my Twitch activity:

After making this graph, I almost stopped watching twitch during studying break. Instead I now often take a small walk, listen to music or do some light streches and exercises.

Even though I don’t have recorded data when making this graph, it is still immensely useful to approximate probability distributions from memory. The exact numbers may be mildly off, but the markov chain and probability distribution representation gives me a decent understanding of the problem. The objective here is to be more productive and the mental approximation works.

Daily recall

Idea and implementation

Daily Recall is another experiment coming out the stat157 project, started on Oct. 20th. It was meant to have a better understanding of what I do everyday, like an explorary data analysis on my daily activities besides studying. If I do lots of small experiments, small bets like this, maybe I could find some something useful in life.

Ideally I am supposed to recall all the activities I do every day sequentially, writing down when I do what, and for how long. However, recalling at granular details will take up lots of time and effort. I was initially often distracted while doing this activity because my brain was resisting to be deeply engaged. After a while I decided to limit the total daily recall time to 10min.

Discoveries

Some small things/events could have big impact on the trajectory of the day (I think that statement could scale into months, years, decades or even centuries). Here are some examples I find from my daily recall activities:

1. Eating the wrong food, such as food that caused me food coma, could make me difficult to concentrate in the afternoon. Thus it takes me longer to start doing work in the afternoon (most of time watching twitch instead). 2. Wasting an hour or two of productivity (e.g talking to my friend when I am supposed to study/work) during the day of deadline will delay my sleep schedule which would both physically wears me down the next day and mentally reduces my productivity momentum.) 3. Exhaustions from my gym session will indeed weaken my willpower hence jeooarduze my evening productivity (given that I don’t workout regularly).

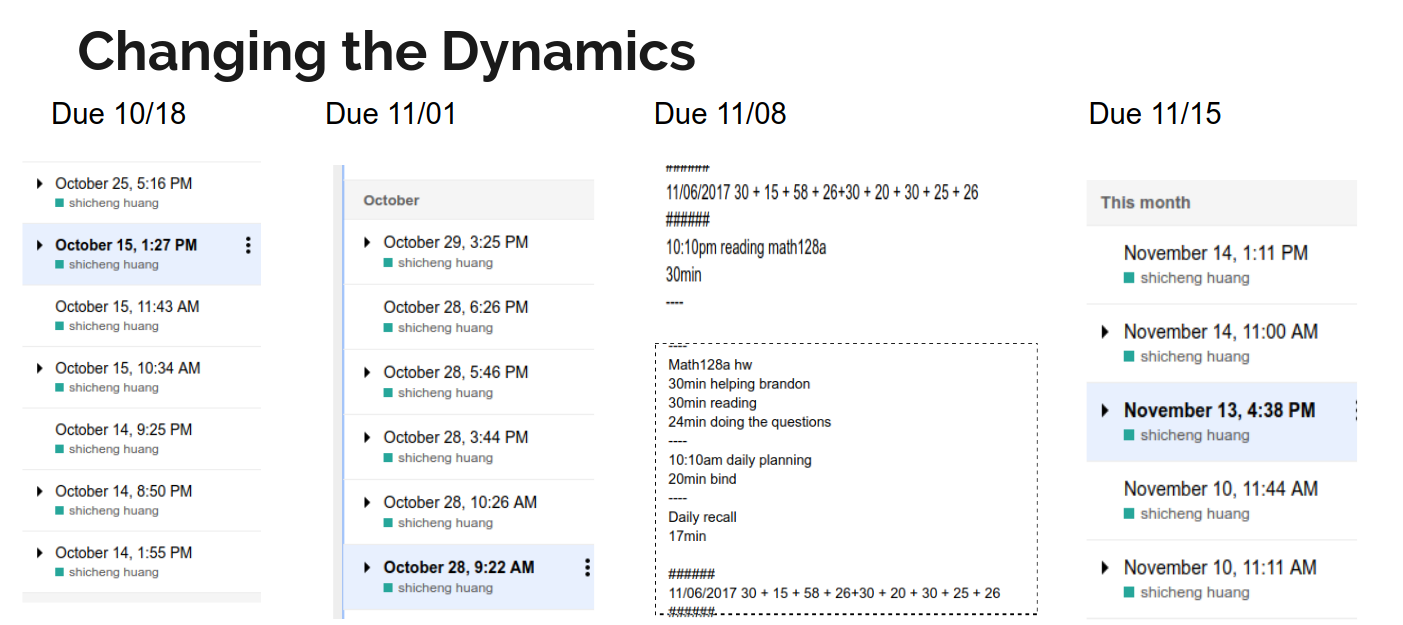

Analysis of math128 homework submission

Desperately trying to get out of survival mode in math128a (i.e doing the homework on the last day), I see the state being ahead in homework submission as a markov chain. Then I hypothesize that, if I get into the state of being ahead on a homework submission, then I am much more likely to stay ahead in the next, or next few homework submissions. Thus I started much earlier on the Oct 18th homework and stayed ahead of the homework schdule ever since.

This hypothesis is not made out of nowhere but from looking back from my academic history. During middle school I was often ahead of the class homework schdule. I thought the power of habit may carry me through the “motivation” needed to combat procrastination.

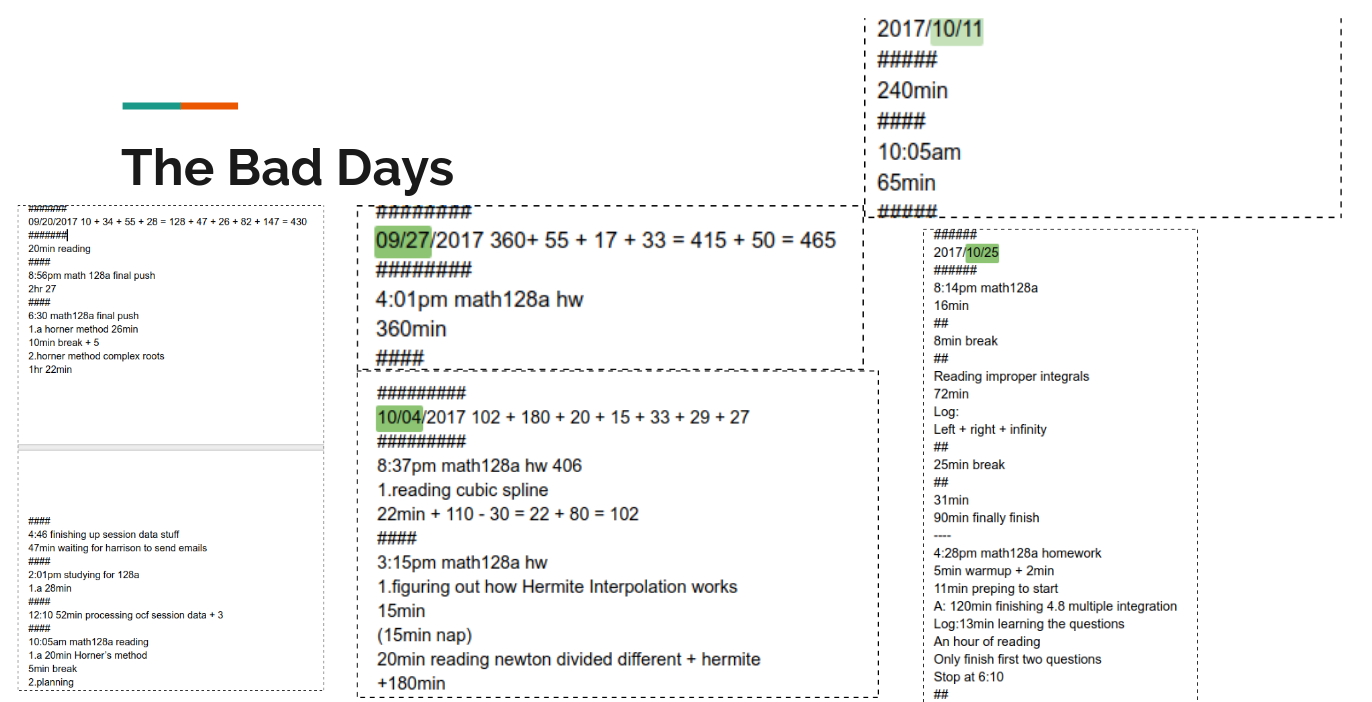

Here is an illustration of the problem through data: Because I keep track of my studying time, I could see the days when I cramped the homework in the last day. Then I would have a spike of “productivity.”

Below are either edit history of my math128a notes (I only read the textbook when I do my homework) and my deep work integration data. You can see I started a few days early almost on all of them except for the homework in 10/25. That is when I had to make a delay due to stat154 midterm.

Big lessons from this project

-

Plans fail most of the time. Most of my plan failed miserably in the beginning. Like many machine learning algoirthms, the initial learning phrase often have many bad results. We should be like the machines when things don’t go well: don’t get disencourage and keep learning until convergence to our goals.

-

”Good resolutions are useless attempts to interfere with scientific laws. Their origin is pure vanity. Their result is absolutely nil. They give us, now and then, some of those luxurious sterile emotions that have a certain charm for the weak…. They are simply cheques that men draw on a bank where they have no account.”

If I have been making the same mistake repeatedly, using bayesian inference, I am expected(“doom”) to make the same mistake the next time. The important part is to think of: What are some concrete elements(new conditions) should exist so that I can behave differently next time?